I’m for truth, no matter who tells it. I’m for justice, no matter who it is for or against. I’m a human being first and foremost, and as such, I’m for whoever and whatever benefits humanity as a whole.

ー The Autobiography of Malcom X

The other day, I came across this juicy thread on Twitter (2) (yeah, I’m on twitter now if you didn’t know). Two people, who started with a disagreement about minimum wage, had a back and forth that quickly escalated into personal attacks and a warzone as opinionated scrollersby joined the fray. By the time I arrived, the initial disagreement was buried so deep I had to do some dedicated snooping just to understand how it started and what it was about. It got me thinking: how did this happen? How does a simple disagreement morph into an all out Hunger Games-esque brawl?

You absolutely are and I know it. Marinate on it for a while. Go ask a person poorer than yourself if they’d be thrilled to have your car and your position for some actual perspective. You speak from an absolute place of privilege. Many people don’t even have a damn car.

— Cyan Banister (@cyantist) March 1, 2020

a particularly juicy excerpt

This kind of thing doesn’t just happen on Twitter (although it is a lot more frequent and pervasive in online communities compared to real life)ーI’m sure you can think of a time in your workplace where you’ve seen two people talk past each other until the original point of contention is lost and they’re left arguing for the sake of arguing. We recognize it because it’s something that we have all done at some point in our lives, even as we joke about how stupid it is when we see other people doing it.

But, wait a minute… we didn’t get into this discussion just to argue, did we? By simply taking a step back, we can often see two people on seemingly opposite sides have much in common: a similar, or at least comparable, belief in how the world should be and a solid investment in the problem to even want to argue with us in the first place. The main difference? The means through which to solve the problem. However, as emotions rise, priorities suddenly shift from wanting to solve the problem into wanting to be right about our opinion of how to solve the problem. We’re swept away by the idea of saving the day with our opinion. Something about it feels so good and necessary. We’re standing up for our thoughts and the rush of fight or flight fuels our attempts at witty takedowns.

Of course, as with all interpersonal things, there’s a lot of nuance here, but one common, important change in these situations is that we shift from an open-minded problem focus to a self-gratifying solution focus. Our pride and desire to be the “hero” has triumphed the unassuming desire to get to the bottom of an issue. While it might not seem like a big deal to want to be a hero (who doesn’t want to rock a cape and tights), this mindset shift means everything. Instead of thinking about how we can work together to solve a problem, as you would do in a group brainstorming or problem solving session, we think about how to undermine the “other” in order to triumph over them. Even the language we use shifts from collaborative and inclusive into combative and divisive.

We start with two groups of people, although holding different stances on the impact of a policy, sharing a common desire to empower and help workers, and we slowly deteriorate into a pissing contest, full of personal attacks and “he said, she said.” Imagine if, instead of spending all this mental effort on status maintenance, we put it towards making the common goal a reality by digging to understand the root of the problem.

Why does it happen that two sets of well-intentioned people, sharing similar goals, end up as opposing battle lines with rifles drawn?

A Hero’s Journey: Name, Shame, and Blame

A key factor of how things went downhill fast is growing enamored with a self-gratifying solution and how easy it is to get emotionally attached to our opinions when we’re trying to save the day. Why is it that we become attached to our opinions?

One take is that our beliefs make up a big part of our identity. Our thoughts and emotions are what make us us. When our beliefs are challenged, the same part of the brain that is associated with personal identity and threat response activates. A fundamental part of who we are is wanting to defend our opinions because we want to be right. It’s also hard to not want to be right when it’s literally physically painful if we’re wrong.

Once we’re attached to our opinions, our rightness is set in stone, and our goal changes from seeking truth to correcting those who think differently than us, those who are wrong. We are our own hero; and as the hero, it’s our duty to defeat the evil naysayers for the sake of the rest of the world. Most mainstream entertainment media feeds this to us, particularly while growing up, in some form of this question: Why is it that bad things happen to good people?

Keanu Reeves plays John Wick with the character’s puppy whose (spoilers) death prompts Wick’s justified destruction of the criminal world. (David Lee)

It’s one that has been asked countless ways in endless time periods. It often follows the tragic end for an innocent or sidekick whom we’ve watched develop. We feel for them because we’ve seen the world through their eyes, their experiences, and their emotions. Our perspective is their perspective, and as a result, we see them as goodーjust like we see ourselves as good. We ask to lament the unfairness of life: theyーweーdon’t deserve this. We ask to absolve ourselves of accountability and retrospection. We were wronged, it’s someone else’s fault, and the protagonist (us) is gonna give them hell to pay soon. Name, shame, and blame.

In the real world, this plays out viscerally in virtue signaling1

The original article that introduces the term makes this case on virtue signaling (excuse the mismatch in spelling; the source is of the OG English variety).

‘virtue signalling’ — indicating that you are kind, decent and virtuous.

…

It’s noticeable

how often virtue signalling consists of saying you hate things

. It is camouflage. The emphasis on hate distracts from the fact you are really saying how good you are.

…

One of the occasions when expressions of hate are not used is when people say they are passionate believers in the NHS. Note the use of the

word ‘belief’

. This is to shift the issue away from evidence about which healthcare system results in the greatest benefit for the greatest number of people. The speaker does not want to get into facts or evidence. He or she wishes to demonstrate kindness — the desire that all people, notably the poor, should have access to ‘the best’ healthcare. The virtue lies in the wish. But hatred waits in reserve even with the NHS. ‘The Tories want to privatise the NHS!’ you assert angrily. Gosh, you must be virtuous to be so cross!

ーJames Bartholomew, The Spectator

(highlights mine)

Essentially, virtue signaling consists of signaling to a group that you believe in some accepted (at least amongst the group) virtue via asserting that you believe in that virtue or admonishing someone or something else that is antithetical to that virtue.

There’s a lesser-known foil of virtue signaling known as vice signaling which covers a whole different category and is explicitly not what I’m referencing in this post because the presence of good intentions is more unclear. It refers to (what I believe to be) the minority of these kinds of cases where the signaler’s bad or selfish intentions far outweigh any good. Suffice it to say, this branch also displays the name, shame, and blame game but in a much more explicit manner of identifying a specific scapegoat, whether it is blaming all Mexicans, Amazon, big businesses, and the ultra-rich, and/or Obama for the downfall of America.

But in the majority of cases, there is clearly some good intent here. Think of a time at the annual family gathering when the topic miraculously drifts into politics again, and in the blink of an eye, the dinner table has transformed into an ideological free-for-all. Maybe you thought about staying quiet (it’s not worth the trouble), but in the end, you and your family members spoke up in part because you care about each other.

Most people speak up in argument because they truly believe in some virtue and want to see it realized. Unfortunately, the easiest path to dopamine hits from feeling like we’re “helping” is advocating for that virtue and naming, shaming, and blaming others who don’t display it. Virtue signaling describes this phenomenon when the good intention and authentic belief in a virtue that is missing from the world become inexplicably tied to something darker, yet 100% human, of judging people based on our interpretation of their reality.

In our current crisis, there’s been a recurring theme in the lack of, fabrication of, and revision of information, even among reputable news sources. Should we wear masks? Should we go hike? Should we go out to eat to support local restaurants? Is the cure worse than the disease? The “right answers” to these questions have changed a lot over the past month, and while we’ve settled somewhereー1) Yes probably 2) Locally in your neighborhood but avoid state parks/beaches 3) Buy gift cards and order takeout instead 4) No Maybe, it depends on the implementation2, but it’s important to consider people’s livelihoods in the resulting economic downturnーthere’s still a lot of open questions that make the answers murkier (what if I live in a remote area of a state park, what about delivery workers, etc.). This climate of rapidly changing information also resulted in a uniquely changing environment for what is considered a virtue. As a result, in the interim and even now, there has been lots of coworker admonishing coworker, friends judging friends, and family berating family, let alone all the random internet persons that have faced anonymous wrath for innocuous actions.

Take for instance this controversial Reddit post, titled “Police Officer confronting two idiots having lunch on a Beach during Quarantine” (looks like it was deleted now but the photo looked like the one below but with a police officer approaching a couple having a picnic).

(Hugo Michiels LNP)

This title reeks of virtue signaling: it names the people on the beach, it shames them by calling them idiots, and it blames them for potentially spreading the virus by not quarantining in the name of the virtue of staying at home. So what do you think? Does this couple deserve to be called out? If you don’t have a clear-cut answer/opinion, you’re not alone. The problem is there are so many things that are dependent on the context that we can’t extract from this photo, so the interpretation we take is based on limited info. Seeing everyone dishing out hot takes on what’s going on makes it seem like we need to have one too, and the path of least resistance is following the crowd. We need to learn that it’s ok to reserve judgment if we can only see parts of the whole and take on the mantle of actually educating ourselves to hold an opinion confidently. Saying this person is defying my notion of virtue and labeling them as evil provides quick and easy validationーwe feel as if we’re doing our part as the heroーbut doing so strips away so much of their humanness. In doing so, we take other human beings and compress them down into narrow, tailored interpretations of what they stand for and believe in.

The tendency to name, shame, and blame comes up even more often in an argument. Once we’re really in the heat of things and the discussion starts breaking down, some part of us suddenly believes that tearing someone else down (relevant or not and valid or not) immediately absolves us of what we are criticized for. The vicious cycle soon takes hold, and there’s no hope of escape until, finally, we arrive at exhaustion. Both sides are exhausted, mentally and emotionally, by the endless cat and mouse and opt to completely detach from the argument as a defense mechanism. In this state, we shut down, and the deadly killer of passion, indifference, takes root. The biggest tragedy is that the start of the discussion was an opportunity to bridge divides, understand differences, and affect change, and it ended up killing whatever fire we had to make a difference in the first place. The exhaustion and resulting indifference tell us, “you tried; it’s just too damn hard.”

Can you see how this happened in the thread? People start digging up dirt about how good the involved persons are at their work or who they are as a person (here’s one discrediting the other side), and pretty soon, that’s the whole story. The minimum wage part becomes the side act, while the question of who is a better person (and therefore has the right opinion) takes the spotlight. And while it seems like there was some empathy acknowledged, it was clearly too little too late. What if they had listened to each other’s points? Would the end have been different?

Caught in the Crossfire

Although it’s already a tragedy when two well-intentioned groups of people end up in a ruthless firefight, there’s another tragic component that is often overlooked. In war, collateral damage refers to “death, injury, or other damage inflicted that is an unintended result of military operations.” Because the two fighters in a war conflict are so focused on defeating each other, they often intentionally or not neglect innocents and third parties who face consequences directly or indirectly from the wartime actions. Unfortunately, collateral damage also occurs in these ideological wars.

In their book, Poor Economics, as they examine the policies that affect the world’s poorest by combining their stories with the data points that claim to represent them, Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo reveal how this situation arises among the world’s foremost experts on poverty. In each chapter, they analyze a specific problem for the poor (food, education, health, etc.) and they present the current state of the world as two sides with opposite perspectives on the problem: one usually more “liberal” of believing in government intervention and foreign aid and the other more “conservative” of believing in market incentives and governmental inefficiency. Two sides, full of well-meaning economists, social scientists, and business leaders, that have spent years arguing about each others' initiatives instead of taking notes from each other and collaborating to come to a better solution. While time is spent talking over each other, positing that the supply curve as a better leverage point than the demand curve or praising the magical efficiency of market incentives, people are still dying from easily preventable causes.

This urge to reduce the poor to a set of clichés has been with us for as long as there has been poverty: The poor appear, in social theory as much as in literature, by turns lazy or enterprising, noble or thievish, angry or passive, helpless or self-sufficient. It is no surprise that the

policy stances that correspond to these views of the poor also tend to be captured in simple formulas

: “Free markets for the poor,” “Make human rights substantial,” “Deal with conflict first,” “Give more money to the poorest,” “Foreign aid kills development,” and the like. These ideas all have important elements of truth, but they rarely have much space for average poor women or men, with their hopes and doubts, limitations and aspirations, beliefs and confusion. If the poor appear at all, it is usually as the dramatis personae of some uplifting anecdote or tragic episode,

to be admired or pitied, but not as a source of knowledge, not as people to be consulted about what they think or want to do.

ーPoor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty

(highlights mine)

Although this conflict more closely resembles a Cold War rather than a bloody battle, the core troublesome elements of the Twitter thread are still present, of two sides failing to listen to what each has to say and adopting the “I’m right at all costs” mentality as the default. However, it’s clear who is the collateral damage in this war. In the midst of the two sides' unwavering standoff, we see how the most vulnerable are becoming casualties of the downstream consequences. As the sides got swept away in their ideals of how the world should work, they neglected a third perspective that was often unrepresented or misrepresented on the global debate stage. Certainly, there is a lack of empathy and understanding between the two sides, but even more so, there is a lack of empathy for those without the opportunity to contribute. The lack of understanding between the two sides is the same phenomena we witnessed before, of a natural degradation to a self-gratifying solution focus, but the lack of empathy for the missing voices is something else entirely. The latter stems from assumptions. Assumptions about the world’s poorest, that were most likely formed from concrete data and anecdotes but an incomplete part of an incomprehensible whole. These assumptions about what affected third parties think, want, and feel are the misfired bullets, imprecise drone strikes, and family separations of an ideological war. Perhaps, if the two sides had gotten together earlier to learn from each other and understand where these assumptions were coming from, they might’ve been able to understand under what circumstances each side’s assumptions held under and when they fell apart.

What’s the collateral damage in the tweet? We see that one side is a former Uber driver and the other is a former Uber investor. It can be tempting to generalize their viewpoints as representative of the whole population, but let’s look for the missing perspectives. Let’s look specifically at the case here of ride-share drivers. What do lawmakers, economists, social scientists think? What about those who don’t have the resources to even begin driving for ride-sharing apps? What do other drivers think and how have they experienced current wages? Where does it fall short and where does it do well?

How do we avoid getting stuck in this trap of zeroing in on a self-gratifying solution? Better yet, how might we enable productive and respectful exchanges of perspective that fuel a virtuous cycle of being open to different thoughts and obsessed over the problem?

The Art of (Ideological) War

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.

ーSun Tzu, Art of War

This problem of our base instincts to avoid dissonance and be the hero derailing our best efforts to solve an important issue is massive at a societal level, and it’s unclear how we even go about tackling it (although maybe some good intentions can come together and make some progress here 😉). But I do have a personal strategy I’ve developed to face ideological warfare. I try to embrace a curiosity mindset. I can hear you thinking: “what is a ‘curiosity mindset?'” I think of it as allowing myself to be consumed by the search for truth when I’m trying to find the answer to a hard question or the best solution for a hard problem. This helps protect me from the natural degradation to arguing for yourself by putting a priority on avoiding emotional attachment to opinions or solutions upfront.

Fundamentally, as Sun Tzu says, it requires knowing yourself and knowing the enemy. Otherwise, you’re certain to face defeat.

Knowing Yourself

What does it mean to know yourself? Part of it involves being brutally honest with yourself and understanding what your implicit and unconscious biases are.

The greatest lie you can tell yourself is that you know best for everything. We don’t know everything, and we need to actively acknowledge that, to avoid any trick our subconscious tries to pull. Regardless of our accolades, years of experience, and ToP (time on podcasts), we can be wrong about things, even things we know very well.

Especially with personalized recommendation systems echoing opinions that we already know or agree with and promising answers to all our questions at our fingertips, it’s easy for us to trick ourselves into thinking we’re aware of everything there is to know. We fall into the mindset of believing that our way of thinking is the only correct way of thinking and that we can easily find the answer to arguments against this way of thinking.

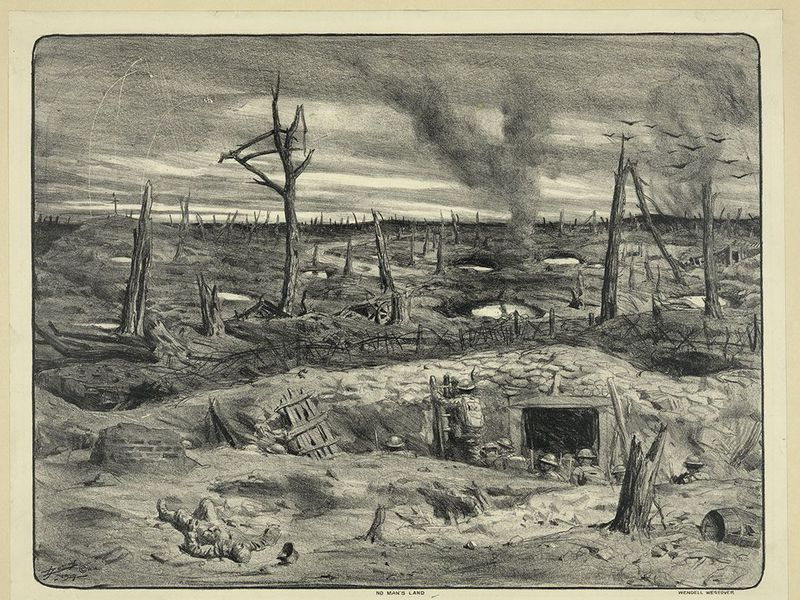

Unfortunately, because emotions are heavily involved in these arguments, there is a lot of variance in what is good or bad even for something that seems straightforward. Life isn’t black and white, and the hardest problems are especially colorful. And while AI-powered search engines promise simple answers to nuanced questions, it’s impossible to come up with an all-encompassing simple answer to these hard questions. We can gather lots of different perspectives to use as tools for coming to a better answer, but it’s not going to be as easy as saying X is bad and Y is good, even if we are programmed as humans to categorize things into neat little boxes for efficiency. We need to have the courage to venture into the murky, grey middle area, the no man’s land of ideological and thought warzones, to find the scraps of nuance that have been overlooked.

A depiction of No Man’s Land; luckily the ideological analog is not as gloomy (Lucien Jonas, 1927, Library of Congress)

A pre-requisite to this resolve is having the humility and forethought to deliberately articulate your own assumptions beforehand and actively test them to see if they’re up to snuff, pruning the ones that don’t pass the test. It also means understanding what you are predisposed to believe or categorize in order to supplement counteracting sorts of viewpoints or thinking. Instead of looking for the answer to end all answers, gather specific information within certain contexts and build your arsenal of mental models (the equivalent of tools for your mind) to increase the number of angles you can approach a problem.

Knowing the Enemy

If you’ve participated (or lurked) in any online arguments, you’ve probably seen the term “straw man” thrown around to attack opposing points. Wikipedia calls it the logical fallacy of “giving the impression of refuting an opponent’s argument, while actually refuting an argument that was not presented by that opponent.” This conveniently fits the name, blame, and shame game. In fact, it makes it even more convenient by giving you an easier point to take apart by ignoring the parts that you find difficult or uncomfortable. With a straw man, you get a bargain deal: avoiding that cognitive dissonance creeping up while validating yourself by taking down your “opponent’s” argument.

A straw man also relies on assuming we know what the opposing side is thinking and feeling. As we’ve seen it’s easy to let our interpretations run wild and for confirmation bias to subconsciously fill in what we want to see to make things fit nicely onto two sides. The alternative is called the principle of charity. It means that we interpret other people’s statements in a way that makes their argument strongest instead of weakest. Essentially, it means to give people the benefit of the doubt when we don’t have all the information (I’ve also liked Hanlon’s Razor as a useful catchy companion to overcoming this cognitive bias)

a cute example of the principle of charity (source)

It’s important to be careful about taking this to the extreme (if you ever have me for more than 10 minutes, ask me about how I lost $800 trying to help a stranger). We can be generous in our interpretation, but we need to verify our interpretations before trusting completely. And of course, there are cases where powerful people or organizations abuse their power repeatedly in a way that sometimes requires a more public and aggressive response to create change.

While a straw man helps us to feel good, it only worsens our ability to persuade and defeat the other side. What if, instead, we decided to actually listen to what our opponents are saying? I know, crazy idea, right? It’s easy for people to “listen.” Usually, when people say they’re listening it means they are listening to respond. Instead of being fully present for what the other person is communicating and internalizing their point of view, a significant part of our mind is turned inward, working to extract which statements to fight back on. We’ve turned someone with an opinion of their own into another opportunity for us to dispense our knowledge.

listening to respond to the extreme (note how listening feels like a misnomer)

And the worst part is that doing so deprives not only the other person of the dignity and respect that their thoughts deserve, but also deprives yourself of the precious opportunity to understand a piece of another living being’s heart and mind.

In order to know our ideological “enemy,” we need to listen to them with an intent to understand. We need to give them and their thoughts the respect and dignity deserved and appreciate their willingness to open up to us. If we do all that right, all that’s left is to be prepared to learn something new that will help inform our view of the subject at hand. Who knows, maybe we’ll actually change our minds about something, after all’s said and done.

So we know ourselves and our enemy, and Tzu says we don’t have to worry about a hundred battles… What about 1000? I’m going to try to offer a third piece of advice that Sun Tzu didn’t capture to hopefully get us even further.

Bridges And Catapults

What more can we do once we’re aware of our own biases and listening to other people?

People often say “build bridges, not walls.” And while I agree and commend the sentiment, I think it doesn’t capture an important scenario. What do we do if we’re already surrounded by walls?

Every day, our brains put up walls around us to block us off from challenges, ideas, and people that cause us a significantly high level of discomfort. Our brain is merely doing what it is evolutionarily programmed to doーto protect us from negative feelings that arise from external stimuliーbut in doing so, incentivizes a world of restriction and fear. We need to fight these natural instincts when they come up and push ourselves to build bridges to the uncomfortable, the different, and the challenging, but we also need to proactively tear down the walls that have stood throughout the ages.

In building bridges, we need to harness the power of the good intent and passion people have to build them up instead of tearing them down. The opposite of a straw man is a steel man, “an improvement of someone’s position or argument that is harder to defeat than their originally stated position or argument.”

Instead of tearing people down, we need to build people up and harness the power of their good intent and passion to work towards the better answer that lies somewhere in the vast middle. We should bias towards building on similarities and reconciling differences as if we’re on the same team working towards the best solution for a common problem. Note that this doesn’t mean we can’t criticize or pick apart people’s ideas or proposals. Building people up and pushing back on things you don’t agree with are not mutually exclusive, despite how often they are misattributed to be.

This also means we need to take catapults to the restricted areas to tear down the ancient barriers that have closed our minds off to ways of thinking different from the circles we frequent. It means listening to and advocating for the innocents that were trapped in these mental prisons when caught in the crossfire of the main argument.

fall of the Berlin Wall in Nov. 1989 (Sipa via AP)

If we’re serious about getting to the bottom of a problem, it’s our duty to find the relevant views that we haven’t captured, and the only way to do that is through taking bridges to uncharted territory. We have to seek people outside our normal outlets of discussion, that so often become mini echo chambers for our ideology. We should treat omission by ignorance as a crime to force ourselves to make up for the info that we don’t have. This also means we have to embrace what Frances Hesselbein, former CEO of the Girl Scouts, phrases as, “you have to carry a big basket to bring something home.” It means we have to embrace the belief that we can learn from everyone regardless of accolades and material status symbols. We need to fill our baskets with as much as we can absorb and take them home to reconcile with what we already believe.

Phew, we got through all of that

What good would these guides have done in that tweet thread, you might be wondering? The first step would’ve been acknowledging that there’re more nuanced answers than the catchy but absolute sound bites like “(raising/lowering) the minimum wage leads to a (better/worse) economy” (insert the choices that work for the argument you’re going for). They could’ve forgone Twitter, where you’re forced to strike nuance in 140 characters, for an actual conversation about each other’s beliefs, assumptions, and values. Armed with that understanding, they could’ve united to articulate points of agreement and disagreement and roped in missing perspectives (social scientists, other gig and minimum wage workers, small business owners, etc.) to move towards a better answer, together.

As the length of this post might indicate, this stuff isn’t easy (well, either that or my writing is incredibly long-winded). The issue is that all of the things we’re trying to pick apartーintent, impact, interpretationーare all emotionally charged, and human emotion is a wild, strange, confusing place. Especially in the current state of the world with COVID-19 hijacking our lives, minds, and hearts, a lot of people are undergoing a huge range of emotions that are difficult to keep up with. And as a result of the large mood swings, I imagine a lot of people are feeling this persistent and all-encompassing feeling of restlessnessーthat when are things going to be back to normal… are they ever going to be back to normal? dichotomyーarising from the constant flood of hopeful, grim, and conflicting new information flowing from our personal devices.

We’re still left with the question of how to tackle this at the society-scale. How might we better harness the power of good intentions to come to a good outcome? Do we need a large societal mindset shift or is there a way to design communication structures that encourage generous interpretations and listening to understand? But I imagine this is something that we can focus on after the world feels safe again.

Regardless, it’s hard to figure out how we should act in a time like this. We start questioning ourselves on things we normally take in stride. Like what should we be spending all our extra time on? What is the socially acceptable way to pass someone on the street? What do I do if my hair grows so long it becomes a monster and starts attacking me? Maybe the last one is just me.

The point is there’s a lot of questions and not a lot of answers, so instead of trying to pretend like everything is ok which our body’s defense mechanism pushes us towards, let’s help the people around us, be more understanding of mistakes, and figure out how we can contribute to our communities.

As one Redditor so aptly put it (in a testament to being able to learn from anyone and anywhere):

It’s tiring seeing so many parrot misinformation & fear based lies. What should be an excellent opportunity for us to reevaluate our communities & roles supporting each other, instead has turned into a free-for-all arguing who knows Truth, & which scapegoat should be associated with their version of Truth.

ーChamberedEcho (source)

Resolve to charge into the muddy, messy middle, really listen and understand others, and build people up while tearing walls down in searching for the answer to a better world, even and especially if they disagree with you.

This means if you disagreed with me or think I was off base at any point in this post, please let me know! I would love to hear your perspective and have a conversation that moves us closer to the better answer :)

Thanks to Avery Jordan for systematically yanking out my inconsistent structural weeds, to Ameesh Shah for the candid brainstorms, and Andee Liao for edits and sharing relevant anecdotes.

-

I know this term is controversial, but I’m using it as a crude way to discuss the kinds of actions I want to talk about and not to imply any kind of moral judgment. ↩︎

-

a recent video that helped change parts of my perspective on this. Also from a purely analytical perspective, Dr. Katz does a great job getting around the pitfalls described in this post by trying to listen to all sides and pushing a nuanced and challenging argument. ↩︎